Friday, November 6, 2009

Early Designs of Turbojet Engines

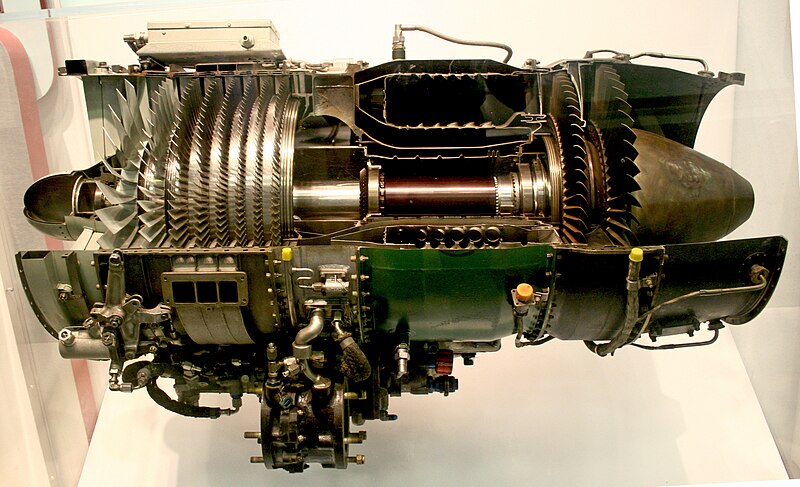

J85-GE-17A turbojet engine from General Electric (1970).

Early German engines had serious problems controlling the turbine inlet temperature. A lack of suitable alloys due to war shortages meant the turbine rotor and stator blades would sometimes disintegrate on first operation and never lasted long. Their early engines averaged 10–25 hours of operation before failing—often with chunks of metal flying out the back of the engine when the turbine overheated. British engines tended to fare better, running for 150 hours between overhauls. A few of the original fighters still exist with their original engines, but many have been re-engined with more modern engines with greater fuel efficiency and a longer TBO (such as the reproduction Me-262 powered by General Electric J85s).

The United States had the best materials because of their reliance on turbo/supercharging in high altitude bombers of World War II. For a time some US jet engines included the ability to inject water into the engine to cool the compressed flow before combustion, usually during takeoff. The water would tend to prevent complete combustion and as a result the engine ran cooler again, but the planes would take off leaving a huge plume of smoke.

Today these problems are much better handled, but temperature still limits turbojet airspeeds in supersonic flight. At the very highest speeds, the compression of the intake air raises the temperatures throughout the engine to the point that the turbine blades would melt, forcing a reduction in fuel flow to lower temperatures, but giving a reduced thrust and thus limiting the top speed. Ramjets and scramjets do not have turbine blades; therefore they are able to fly faster, and rockets run even hotter still.

At lower speeds, better materials have increased the critical temperature, and automatic fuel management controls have made it nearly impossible to overheat the engine.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment