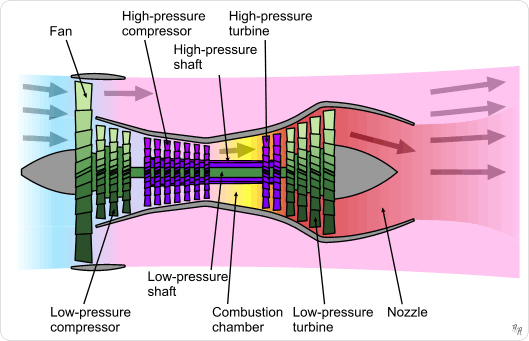

The major components of a jet engine are similar across the major different types of engines, although not all engine types have all components. The major parts include:

Cold Section:

Air intake (Inlet) — For subsonic aircraft, the air intake to a jet engine consists essentially of an opening which is designed to minimise drag. The air reaching the compressor of a normal jet engine must be travelling below the speed of sound, even for supersonic aircraft, to allow smooth flow through compressor and turbine blades. At supersonic flight speeds, shockwaves form in the intake system, these help compress the air, but also there is some inevitable reduction in the recovered pressure at inlet to the compressor. Some supersonic intakes use devices, such as a cone or a ramp, to increase pressure recovery.

Compressor or Fan — The compressor is made up of stages. Each stage consists of vanes which rotate, and stators which remain stationary. As air is drawn deeper through the compressor, its heat and pressure increases. Energy is derived from the turbine (see below), passed along the shaft.

Bypass ducts — Much of the thrust of essentially all modern jet engines comes from air from the front compressor that bypasses the combustion chamber and gas turbine section that leads directly to the nozzle or afterburner (where fitted).

Common:

Shaft — The shaft connects the turbine to the compressor, and runs most of the length of the engine. There may be as many as three concentric shafts, rotating at independent speeds, with as many sets of turbines and compressors. Other services, like a bleed of cool air, may also run down the shaft.

Diffuser section: - This section is a divergent duct that utilizes Bernoulli's principle to decrease the velocity of the compressed air to allow for easier ignition. And, at the same time, continuing to increase the air pressure before it enters the combustion chamber.

Hot section:

Combustor or Can or Flameholders or Combustion Chamber — This is a chamber where fuel is continuously burned in the compressed air.

Turbine — The turbine is a series of bladed discs that act like a windmill, gaining energy from the hot gases leaving the combustor. Some of this energy is used to drive the compressor, and in some turbine engines (ie turboprop, turboshaft or turbofan engines), energy is extracted by additional turbine discs and used to drive devices such as propellers, bypass fans or helicopter rotors. One type, a free turbine, is configured such that the turbine disc driving the compressor rotates independently of the discs that power the external components. Relatively cool air, bled from the compressor, may be used to cool the turbine blades and vanes, to prevent them from melting.

Afterburner or reheat (chiefly UK) — (mainly military) Produces extra thrust by burning extra fuel, usually inefficiently, to significantly raise Nozzle Entry Temperature at the exhaust. Owing to a larger volume flow (i.e. lower density) at exit from the afterburner, an increased nozzle flow area is required, to maintain satisfactory engine matching, when the afterburner is alight.

Exhaust or Nozzle — Hot gases leaving the engine exhaust to atmospheric pressure via a nozzle, the objective being to produce a high velocity jet. In most cases, the nozzle is convergent and of fixed flow area.

Supersonic nozzle — If the Nozzle Pressure Ratio (Nozzle Entry Pressure/Ambient Pressure) is very high, to maximize thrust it may be worthwhile, despite the additional weight, to fit a convergent-divergent (de Laval) nozzle. As the name suggests, initially this type of nozzle is convergent, but beyond the throat (smallest flow area), the flow area starts to increase to form the divergent portion. The expansion to atmospheric pressure and supersonic gas velocity continues downstream of the throat, whereas in a convergent nozzle the expansion beyond sonic velocity occurs externally, in the exhaust plume. The former process is more efficient than the latter.

The various components named above have constraints on how they are put together to generate the most efficiency or performance. The performance and efficiency of an engine can never be taken in isolation; for example fuel/distance efficiency of a supersonic jet engine maximises at about mach 2, whereas the drag for the vehicle carrying it is increasing as a square law and has much extra drag in the transonic region. The highest fuel efficiency for the overall vehicle is thus typically at Mach ~0.85.

For the engine optimisation for its intended use, important here is air intake design, overall size, number of compressor stages (sets of blades), fuel type, number of exhaust stages, metallurgy of components, amount of bypass air used, where the bypass air is introduced, and many other factors. For instance, let us consider design of the air intake.

A blade with internal cooling as applied in the high-pressure turbine.

No comments:

Post a Comment